11-Rewriting the Unthinkable: (In)Visibility and the Nuclear Sublime in Gerald Vizenor’s Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57 (2003) and Lindsey A. Freeman’s This Atom Bomb in Me (2019)

. These literary scholars are interested in “the commitment of the sublime notion of crisis” or the sublime as a way of “imagin[ing] total annihilation” (Ferguson 1984, 7). More specifically, there is a “posthumous perspective” in the sublime moment, Ferguson and Richard Klein argue, inasmuch as the terror first experienced in the face of the sublime object contemplated in classical theories of the sublime—be it an overpowering natural landscape or the overwhelming pending threat of a nuclear war—is then transformed into what Kant refers to as “aesthetic well-being” or the “immense pleasure of confronting the greatest forces, the vastest distances in the universe, and surviving, quite deliciously, unharmed” (Klein 2013, 85). What they suggest, however, is that, in the sublime moment, danger or threat is never truly experienced but merely imagined as the emblematic unthinkable or unspeakable (Ferguson 1984, 6), and therefore never treated as a tangible or materialized object or reality.Introduction: “We Must Somehow Articulate or Image-Forth this End-Game Genre of the Nuclear Sublime”

material—the simulated or the sustainable” (Rozelle 2006, 2, emphasis added). Although it might be humanity’s fate to live both in the simulated and the sustainable, the nuclear sublime still strongly leans to the former and not the latter, and specifically emerges in the United States as “the American commonplace or common sense of an unspeakable force that cannot be—by any power of the imagination, however transcendental, overcome” (Wilson 1989, 410, emphasis added). As a result, Wilson encourages writers, poets, and literary scholars to “articulate or image-forth this end-game genre of the nuclear sublime, with all of our collective resources of language and wit” (416) or, in other words, to find an imaginative way of overcoming the deceitful aesthetic mode of the nuclear sublime and of speaking, unveiling its destructive force.

Peter B. Hales furthers Wilson’s take on the nuclear sublime by emphasizing that the mushroom cloud and the nuclear sublime have become both unthinkable and quotidian, that is “so deeply imprinted in the myths and matrices of the postwar era that it has come to seem natural, a fundamental, even a necessary aspect of everyday life” (1991, 5). Hales analyzes a series of American photographs—mainly from Time, Life, and Newsweek—which shows the impactful visual potential of the nuclear sublime and thus remains “profoundly aesthetic, rather than ethical, moral or religious in tone” (1991, 9).2 More precisely, Hales highlights the confusing absence of a notion of responsibility, which he describes as characteristic of both the natural and the nuclear sublime in which “no ultimate responsibility need be taken” by the “American man” (16). Besides, he also touches upon the notion of “terrible beauty,” which is particularly relevant to any understanding of the complex and paradoxical nature of the nuclear sublime inasmuch as “terror and beauty, together, begot a terrible beauty, one that needed the guiding hand of an authoritative and authoritarian military father-figure” (19). Terrible beauty, at least in Hales’ account of the atomic sublime, confuses (or obliterates) the subject’s sense of responsibility: it aestheticizes the bomb and radiation or, as Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 movie title would put it, it makes you “stop worrying and love the bomb.” The nuclear sublime also borrows from the natural sublime in that it involves visual and distant observation of atomic phenomena. For example, Hales explains, Americans did not have to witness the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings since they “occurred at a safe distance from American shores.” (1991, 20). Even the tests executed in American deserts contributed to shaping the mythos of an “uninhabited” and yet “stunning” and “sublime landscape” (20) while, as Joseph Masco argues, Americans were both “aggressors and victims” because they were also exposed to the physical dangers associated with the explosions (2006, 60–66). What is more, the powerful and terrible beauty of the “atomic explosion” overcomes the weird or gothic imagination of transformations into irradiated monsters because “no gothic horror, it seems, could eradicate its majestic beauty, its resonance with the numinous, Absolute, its freedom from moral imperatives” (25).

(2005, 32). Representations of these forms of environmental disruption therefore run the risk of aestheticizing the industrial and capitalist systems that induce them and of minimizing their effects through sublimation (Fressoz 2021, 290). In other words, they may reveal the limits and dangers but also the affordances, of what can be expressed, interpreted, and studied in terms of the sublime, visibility/invisibility, and presence/absence, especially if visibility is achieved when the object or phenomenon is physical or material. Apart from Lippit and Shukin, several critics have attempted to study the nuclear and radiation in relation to light and/or (in)visibility. Elizabeth DeLoughrey, for example, expands the notion of “heliography” to refer to “the discursive practice of writing about light as well as [to] the inscription of our bodies as they are created, visually ordered and perceived, and penetrated by radiation” (2009, 484). Such a materialist and ecocritical approach was later further developed in the works of other (eco)critics such as Molly Wallace (2016), Jessica Hurley (2020), and Fiona Amundsen and Sylvia C. Frain (2020), who have sought to counter the nuclear sublime by veering toward new orientations in nuclear criticism. Building on Wallace’s “materiality of risk” (2016, 15), Hurley proposes the concept of “the nuclear mundane”, which “makes the nuclear visible both in its extent and reach into every aspect of everyday life and in its contestability, as something that can be named and challenged” (2020, 9, emphasis in original). In addition, the “nuclear mundane” better integrates “postcolonial theory” and tries to account, as opposed to notions such as “nuclear universalism” (Yoneyama 1999) and “nuclear exceptionalism” (Hecht 2010), for the significant impact that nuclear technologies have had “on Indigenous land” as well as on “poor communities and communities of color,” (3–16) a concern that is in line with Gerald Vizenor’s critique of dominant cultures that this essay will discuss in the next section. Hurley, but also Amundsen and Frain, evidence the necessity in the field of environmental humanities—as well as in related fields such as nuclear, postcolonial, and Indigenous studies—to deconstruct the “control of visibility” exerted by the U.S. government when it comes to nuclear damage while rendering “visible the overwhelming invisibility of Indigenous experience” (Amundsen and Frain 2020, 126–41). Reimagining the nuclear, in other words, forces us to go beyond the aesthetic project of making atomic phenomena visible by critically interrogating the literary inflections of the sublime as well as by evaluating the various ways through which such phenomena can be made textually visible and interpreted, be it by means of the sublime or of other (complementary) rhetorical strategies and methods.

In this essay, I consider the genres of the experimental novel and the creative memoir as resourceful sites for investigating the affordances and limits of the sublime as a strategy for representing (and critiquing) environmental changes and toxic phenomena such as nuclear disasters and radiation. The first section will undertake an analysis of Native American (Anishinaabe) writer and scholar Gerald Vizenor’s experimental novel Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57 (2003). Hiroshima Bugi has been defined as a “kabuki novel” because its sections involving the character of Mifune Browne, also known as “Ronin,” “depend on highly dramatic scenes, elaborate imagery, and stylized expressions analogous to that which would be used in traditional Japanese kabuki theater” (Jimenez 2018, 267). Ronin’s sections are also followed by narratives by Manidoo Envoy, which offer explanations on Ronin’s performances in the “Hiroshima Bugi,” the kabuki theatre that he designed. In what could be termed “a spirit of experimentation” (Bergthaller et al. 2014, 273), Vizenor deploys complex metaphors drawing on both Anishinaabe and Japanese traditions and conceptual neologisms as means of rendering and critiquing the multifaceted history of the nuclear and the elusiveness of its (sublime) aesthetics.4 Through a rhetorical and narratological analysis of Vizenor’s novel, this essay will question the expressive and critical potential of highly figurative language when used to describe or even condemn the absence of responsibility that is produced by the rhetoric of the atomic sublime.

In the second section, this essay will turn to Lindsey A. Freeman’s memoir This Atom Bomb in Me (2019). As inevitably human-centered and descriptive of “an extra-textual reality” in a dynamic that “is actively constructive rather than passively mimetic” (Couser 2011, 55–74), memoirs are promising case studies to analyze the contemporary rhetoric of the nuclear sublime. More specifically, Tom Lynch’s conceptualization of the memoir as an “eco-memoir” that “involves the writing of self into place and place into self” suggests that the memoir is “an ideal genre for the cultivation of an ecological awareness and bioregional identity” (Lynch 2020, 119). While, as Couser argues, the main affordances of memoir are that it can “immortalize—or at least memorialize—actual people” and “accuse and condemn” destructive behaviors, this eco-memoir helps to “memorialize” irradiated places and make them matter to readers in their attempt to critique ecologically irresponsible behaviors. In other words, while the conventional memoir focuses on an individual’s Bildung, the eco-memoir also revolves around place-building—or world-building—and often by reexploring places that may have been neglected or forgotten. Inspired by new materialist trends and concepts in the environmental humanities such as “vibrant matter” (Bennett 2010) and “trans-corporeality” (Alaimo 2010), which view humans as constantly “intermeshed” (Alaimo 2010, 2) with non-human materiality, author and sociology professor Lindsey A. Freeman writes what she terms “sociological poetry” (2019, 7), or what could be defined as memoiristic prose fragments or vignettes. Freeman’s vignettes are reminiscent of Roland Barthes’s Mythologies (1957)—to which she also frequently refers—especially because she tries to dissect the meaning of the various but related atomic symbols of her hometown, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Through a rhetorical and narratological analysis of Freeman’s recent memoir, this article will show that the previously discussed myths and dangers, namely aestheticizing through terrible beauty or “petrified awe” (Shukin 2020), which may have the effect of disempowering the subject and causing the absence of a sense of responsibility, mainly persist because of the connection between the self and the toxic place that is established by means of the genre of the eco-memoir. Freeman, however, offers leads to alternate, new materialist approaches that seek to complicate and enrich the nuclear sensorium (of Oak Ridge) by involving both “higher” senses (sight and hearing) and “lower” senses (touch and smell), and by linking and discussing mixed (but interrelated) feelings and affects customarily associated with the sublime and the Anthropocene such as overwhelm and confusion (Purdy 2015, 421).5

Together, Vizenor’s experimental novel and Freeman’s eco-memoir formulate a critique of the nuclear sublime as an aesthetic mode because it does not account for the problematic and, as Hurley (2020), Amundsen and Frain (2020) have also claimed, multicultural complexity of atomic culture and history. On the one hand, the experientiality of Vizenor’s novel, which combines intricate metaphors with rich references to non-dominant cultures, sheds light on the complexity of the nuclear as an object of colonial domination over Indigenous people, thus showing what highly metaphorical language and other cultures can to do to deconstruct the aesthetics of the nuclear sublime. On the other hand, Freeman’s memoir possesses a “referential relationship to the real” that is similar to photographs’, which she also includes, but that is complemented by the rhetorical potential of her text which, although it also relies on the author’s memory, expands the “limits of representation” to verge on critical analysis (Amundsen and Frain 2020, 130). Both works suggest that the nuclear sublime simplifies the atomic sensorium and the emotional as well as affective responses to nuclear phenomena by only conveying fascination or “lightheaded amazement” (Wilson 1989, 416) without creating any senses of responsibility or of environmental awareness, and thus engage in more effective forms of socio-political and ecological criticism.

I. Denouncing Destruction and Dominance: The Ethics of Absence and the Natural/Nuclear Sublimes in Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57

, this section analyzes Vizenor’s use of complex metaphors as a means of enriching our understanding of what can be considered as absent or invisible, which also further complicates discussions on dominant/non-dominant cultures as well as “the pursuit of visibility” that the nuclear sublime aestheticizes and obscures through its terrible beauty.

Due to the complexity of the novel and to help us better understand Gerald Vizenor’s imaginative take on nuclear history, this section starts with an overview of the novel’s main characters, structure, and context before undertaking a closer narratological and rhetorical study of the author’s metaphors and use of the sublime as related to the presumably dichotomous notions of presence and absence. Set in the post-World War II era, the novel alternates between chapters in which Ronin Browne narrates what he does in Hiroshima and elaborates on his critical obsession with its Peace Memorial, and others told by Manidoo Envoy. The two first-person narrators meet as Ronin searches for his father, whom he never met, and they spend a month living together at the Hotel Manidoo, “a hotel of perfect memories for wounded veterans” such as Ronin’s deceased father and his friend Manidoo Envoy (Vizenor 2003, 8). While Manidoo Envoy is described as a Native American, Ronin is a hafu, half Japanese and half foreign, in this case half Native American. Ronin’s mother, Okishi, was a Japanese woman, a boogie (hence the bugi in the title) dancer, and his father, Orion Browne, also known as Nightbreaker, was a Native American stationed in Japan as an interpreter at the end of the Second World War. Ronin became an orphan during the war and was adopted by the White Earth Reservation in the United States.6 While the Manidoo Envoy chapters provide biographical and background details as well as sources to support Ronin’s complex metaphors on Hiroshima and nuclear disasters, Ronin’s sections describe his return to Hiroshima as an adult.

As Chris Jimenez explains, “‘Hiroshima’ has become a central starting point by which readers may begin to comprehend the terrible implications of the nuclear age” and “literary practice—even in its disfiguration—is a vital means by which Anglophone writers [such as Vizenor] manage and recuperate from nuclear disaster” (Jimenez 2018, 264). In his article, Jimenez makes a series of points on the global aesthetics fostered by Vizenor, the juxtaposition of abstract with academic writing, Vizenor’s concepts of “survivance” and “victimry,” and dark tourism. Ronin’s chapters, he explains, consist in the “historical aestheticization of nuclear disaster” insofar as they heavily rely on “highly dense language with suggestive but opaque visual language and obscure literary and cultural references” (268). In order to aestheticize nuclear history, Vizenor makes use of several metaphors in Ronin’s sections, including the images of the “ghost parade” of dead children or hibakusha, a Japanese term used to describe the people who were affected by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki explosions and radiations, the “black rain,” the “invisible tattoos,” and the chrysanthemum flowers. The metaphors also relate to Ronin’s approach to death and to the emotion of fear, which are fundamental to our understanding of Vizenor’s treatment of presence and absence. Indeed, such a view of death and fear infuses the metaphors with intricate meaning, I argue, so they do not (only) rely on mere (over)aestheticization of nuclear history and/or phenomena.

“Besides the “fear of death,” which appears as a Western/Christian (e.g., because of the judgement in the afterlife in Christianity) and destructive product in the novel, the image of the “black rain,” caused by the A-bomb explosion, is depicted as responsible for exposing people to radiation and for stealing away the “natural fear of thunder” and the “pure pleasure of rain” (78). What Ronin describes as a “natural fear” suggests a positive emotional response to natural phenomena such as rain and thunder, which has been replaced by the Western negative fear of death. In a way suggesting a shift from the natural to the nuclear or even toxic/poisonous, Ronin adds that “Hiroshima was incinerated by a nuclear thunderstorm, and the hibakusha were poisoned by the rain” and then the children resurrected as ghosts (78, emphasis added). Besides the obvious radioactivity of the “black rain” that is said to have fallen after the atomic bombings, Ronin alludes to the “black rain of culture”, an allusion that is directly followed by a reference to Western/Christian symbology: “No, not the ecstatic fear or perverse pleasure of stigmata. There was nothing aesthetic to bear by reason or creative poses” (4). In this short extract, Ronin associates the ecstasy and overwhelming affects customarily associated with the apparition, be it visible or invisible (e.g., feeling the pain of the wounds without any external mark), of the stigmata with the negative emotions of “fear”, which is reminiscent of the sublime, and “perverse pleasure”. Instead of relying on the aesthetics of the stigmata of a “religion based on reason” (Velie 2008, 157)—i.e., “nothing aesthetic to bear by reason”—, Ronin avoids the pervasiveness of “the black rain of” Western and/or Christian dominant cultural traditions by suggesting that his art builds on a significantly different one.7

Interestingly, the kami spirits (i.e., gods or spirits in Japanese Shinto) are inseparable from the nonhuman insofar as Ronin “presents the sentiments of humans, animals, and birds in the same sense of moral reality” (64). The kami spirits are also reminiscent of the natural sublime since Manidoo Envoy describes them using various words from the rhetoric of the sublime such as “the spirits of a vast, eternal nature” which are “superior,” “venerated at many shrines” and “courted as unworldly visitors” (63, emphasis added). The shrines produce, Manidoo Envoy adds, “transcendent powers, a sense of continuity, stability, and the management of uncertainty,” while “Ronin is a master of uncertainties and survivance” (63, emphasis added). What Vizenor describes by means of the kami spirits and such nouns and adjectives is an overpowering natural sublime that suggests a fraught relationship between superior animate natural spirits and humans. More precisely, he refers to such natural sublime phenomena as a “moral reality,” thus again conjuring the idea of an inspirited ethical power which contrasts with the dominant nuclear sublime. Although it produces other tensions and power relations between humans and nonhumans, Vizenor’s spiritual version of the natural sublime appears as a more viable and less dominant counterpart of the nuclear sublime because the kami spirits produce a sense of moral responsibility itself conflated with a sense of reverence toward the non-human spirit.

This version of the natural sublime is mainly expressed through the trope of “natural presence” as opposed to the “death by silence” (4). The contrast provided by the image of the chrysanthemum flowers is particularly pertinent here since, in some countries, these flowers are placed in cemeteries after someone passed away whereas, in the novel, they are sold in front of the peace memorial. More specifically, the phrase “death by silence” echoes the “passive peace” as well as consumerism since homages (such as flowers) and diplomatic gestures, in Ronin’s sense, only obscure and make us forget about the responsibility of dominant nations and cultures. This responsibility can be explicit (e.g., for the destructive use of nuclear weapons) or more abstract (e.g., for the erasure of other traditions from Anishinaabe or Japanese cultures). In contrast, Manidoo Envoy explains that “Ronin wears invisible tattoos as marks of singularity of the ghosts of atomu children, as invisible as his tattoos, and to honor hibakusha survivance” (104). The concept of survivance is particularly relevant in this extract inasmuch as it is related to Vizenor’s representation of absence and presence, as he explains in a book chapter entitled “Aesthetics of Survivance: Literary Theory and Practice”: “Native Survivance is an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion,” it is the “continuance of stories, not a mere reaction,” and “survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, detractions, obtrusions, the unbearable sentiments of tragedy, and the legacy of victimry” (2008, 1). Survivance, Manidoo Envoy confirms, is a “vision and vital condition to endure, to outwit evil and dominance,” it is “wit, natural reason, and ‘perfect memory’” and ensures “tragic wisdom” (36). “Natural reason,” he says, “is an active sense of presence, the tease of the natural world in native stories” or “the use of nature, animals, birds, water, and any transformation of the natural world as direct references and signifiers in language” (36). “Perfect memories” or ethical representations of nuclear history proliferate through the objective experience of natural reason so that it can become “collective memory” (Vizenor 36). The latter could in turn be interpreted itself as a form of “effervescence collective” (Durkheim 1990, 301) through which individuals and their own subjective memories complete each other so the collective process of memory-making results in a more accurate, “exact imagination” (Vizenor 36) of nuclear history. What the numerous metaphorical compounds suggest is that “survivance” is guaranteed through what Ronin understands as an accurate and non-dominant account of nuclear history.9 In this process, figurative literary language plays an essential role in producing “exact imagination,” and such language is directly inspired by natural elements themselves described in terms evocative of the natural sublime.

As Manidoo Envoy puts it, Ronin’s “chance and tricky metaphors are the traces, the actual connections, and not a separation of the authentic” since “the perception of the real must be sincere” (69), thus bridging the ontological gap between the physical or present and the unreal or absent. By means of complex metaphors and cultural references, Hiroshima Bugi displays how power differences influence the way we experience and perceive the natural or nuclear sublimes as well as nuclear history. As a consequence, countering or defeating the nuclear sublime could involve or even require a complex process of decolonization, of deconstructing relations between dominant and minoritarian groups. In addition, the novel emphasizes that (Western) ontological limitations which establish strict distinctions and separations between the real and unreal, the physical and abstract, and presence and absence could obstruct any “spirit of experimentation” or, in other words, any attempt to imagine viable alternatives to the potentially dominant and destructive aesthetic and rhetoric of the nuclear sublime. While “survivance” is a rhetoric of constructive, collective remembering, the nuclear sublime may invest a beguiling but dangerous aesthetic and rhetoric of effacement which removes any sense of responsibility.

II. Unveiling Secrets and Risks: Invisibility and the Nuclear Sublime/Sensorium in This Atom Bomb in Me

Lindsey A. Freeman’s approach builds on theories from the burgeoning subfield of new materialism which both further problematize the nuclear sublime while offering another materialist account of the presence/absence dichotomy deployed by means of different narrative techniques made possible by the genre of the creative memoir. In This Atom Bomb in Me, Freeman conveys memories of her childhood and upbringing in Oak Ridge through a sociological approach to writing. Oak Ridge, also known as the “Secret City,” is a city in Tennessee of about thirty thousand inhabitants that is (in)famous for serving as one of the three sites of the Manhattan project built to create the world’s first atomic weapons. Freeman also adds that it became a place where most nuclear weapons were and are being built, and “a center for medical research, nuclear storage, national security, and the emergent nuclear heritage tourism industry” mostly thanks to the “Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and the Y-12 National Security Complex” (2019, 6).

As she explains from the very beginning of her memoir, the city is full of symbols that revolve around atomic power such as the “atom-acorn assemblage” (image 1) which is “the totem of the town” that “marks a shared culture and sweeps [its inhabitants] in its substance” (1–2). More precisely, Freeman describes the atom-acorn as representative of the past, present and future of Oak Ridge, thus highlighting the lasting and pervasive potential of atomic power, as can be read in the following quotation: “The atom-acorn is a concentration of all the Oak Ridges that have happened, never happened, might happen, and are happening, combined with the ways in which we have made sense of these happenings” (2). Interestingly, the “totem” incorporates traditional elements of the natural/visible sublime, namely the oak leaves and the ridge lines of hills, and an abstract representation of the unseeable/atomic sublime, that is the atom, both against a stylized background of an ambiguous sunrise or nuclear explosion. Freeman then verges on new materialist thinking by claiming that “the atomic sensorium” (6) is interconnected or entangled with human and non-human permeable corporealities.10 “I carry it in my body,” she concludes, “it is both outside and inside, material and immaterial, pulsing and still” (6). What she wants to explore, she explains, are the “affects” related to an “overwhelm[ing]” atomic culture as well as methods for “thinking and writing that tries to perform both the visible and invisible” (9–10). In other words, nuclear culture and the “atomic sensorium” are described as what Timothy Morton terms “hyperobjects,” or often invisible and pervasive “things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans” (Morton 2013, 1) such as air pollution or global warming, which she endeavors to apprehend and critique through her writing.

Freeman’s memoir unfolds as a series of different but related vignettes respecting a loose narrative arc which both reconstructs the author’s memory and complicates the problematic of the nuclear sublime. One of the first topics, already discussed in her short introduction, is the contrast between visibility and invisibility. Freeman first alludes to this opposition in the vignette “Mister Rogers’ Arms Race” by means of a quotation from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince used by Mister Roger in his TV program “Conflicts”: “that which is essential is invisible to the eye” (21). This quote can be compared with another one from Toni Morrison, mentioned in “The Ghost of Homecoming,” suggesting that “invisible things are not necessarily not there” (46).11 Throughout the narrative arc, Freeman makes use of the invisibility/visibility, absence/presence, and whiteness/color dichotomies. In the same vignette, for example, she narrates how her grandmother used to conceal her mother’s former dates on photographs with “Wite-Out,” a practice which she found both “hilarious” and disturbing (45–46). Comparing whiteness with Mondrian’s paintings of white squares, Freeman explains that she “hated” white because “the white marked the end for those spaces—they would be white and nothing else” and therefore her “mother would only have [her] father and no one else” (46). While whiteness creates “exaggerated absence,” with which Freeman associates a troubling and uncomfortable feeling, colors do not (46).

In “Two Photographs, March and April 1968,” Freeman further explores the notion of whiteness as dissimulating the risks associated with the nuclear in reflections on two black-and-white photographs of the truck her “grandfather drove during his tenure as an atomic courier for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)” (88), which both position themselves in relation to the rhetoric of the sublime.

(image 3), taken from a “distance” which resolutely builds on the rhetoric of the (nuclear) sublime by giving “a real sense of the vehicle’s size and length, something that would not have been grasped from the first photo alone” (88), on which the truck is much closer.

The unidentified black effect below the truck also “heightens the unknowableness of the image” (88), highlighting “the absolute mystery of what is inside” the truck (90). Echoing “The Ghost of the Homecoming,” the truck is then referred to as an “enormous Wite-Out bottle on wheels” which, complemented by the rhetoric of the traditional sublime (“unknowableness,” “absolute mystery,” “enormous”), obscures the dangers of its radioactive content through whiteness.

Allusions to a form of dangerous mystery reminiscent of the nuclear sublime and of its distinctive features of invisibility, secrecy/mystery, and terrible/overwhelming power are included throughout the book and, unlike what the photographs interpreted above suggest, are sometimes presented in a way that allows the possibility of unveiling the risks associated with the nuclear. In the vignette “Carl Perkins,” for example, Freeman evokes how, in “the Manhattan Project days,” the city of “Oak Ridge was absent from commercial maps” and how Perkins, the rockabilly icon, “avoided naming the city in his song,” which to her “made the city more powerful, a secret once again” (60). Then, in “Katy’s Kitchen,” she discusses the eponymous secret project of a storage unit for uranium disguised as “a mysterious blue barn with an odd concrete silo at its hip,” which stresses “the hidden potential of the terrible material swarmed and nested in [her] imagination,” to such an extent that she “learned to question every barn, every seemingly benign structure dotting atomic Appalachia” (62). The vocabulary used in these descriptions often borders on the rhetoric of the sublime inasmuch as words such as “hidden,” “terrible,” “mysterious,” and “powerful” appear as fit for characterizing military endeavors to keep the Manhattan Project secret. The objects described—the trucks, Carl Perkins’s song, the blue barn—provoke mixed feelings of repellence, fascination, and suspicion. The “Space Dogs” vignette exemplifies this ambivalence even more explicitly as here she claims that she was “both repelled and fascinated” by the story of Laika, the Russian dog that was sent to space, while she “couldn’t help thinking of [her own dog] Pepper in space, wondering about his chances out there” (53). Such contradictory feelings are produced in what I term the conspicuousness of risk, a moment characterized by the partial unveiling or debunking of the nuclear sublime through literary inquiry into affects, emotions, and feelings, which results in the undermining or diminution of the nuclear sublime’s emblematic power of concealing danger and risk. Interestingly, it is the rhetoric of the sublime itself that Freeman deploys to investigate the intricacy of these affects, emotions, and feelings which threaten the mythos of the atomic sublime. Indeed, because the sublime seems to fascinate Freeman, it functions as an incentive for her critical interrogation of the risks and dangers associated with atomic power and culture.

The sublime, however, is not the only aesthetic category Freeman refers to in her memoir. Echoing the weird through concerns over “strange” (Fisher 2016, 8) transformations of non-human bodies into monstrous beings, Freeman explains in the vignette “Expecting the worst, not getting it” that her expectations of irradiated deer as “radioactive monsters”—a phrase she uses in a description of a “Recurring Dream” as they have “undergone a nuclear metamorphosis after eating radioactive fish” and turned into “hideous beings, shuffling, zombie-like creatures” (45)—turned out to be false insofar as she witnesses a deer being born and describes it as a “beautiful spectacle” (59). In this passage, the weird has replaced powerful nuclear sublime affects insofar as references to metamorphosed “hideous” and “zombie-like” creatures “denaturaliz[e]” social realism to create an imaginary that no longer produces awe or fascination (Fisher 2016, 107). Such weird imaginary, however, is the produce of the broader mythos of the atomic sublime and the nuclear sensorium suggesting that exposure to radiation will transform animals and people into horrid monsters. In “Radioactive Frogger,” for instance, Freeman explains that the nuclear sublime imagination reached a larger audience when, in 1991, “about one hundred radioactive frogs escaped from a pond containing legacy nuclear waste from ORNL” and the public was “disappointed” when the frogs looked like regular frogs especially after the exaggerations of the press and of folk singer Fred Small, who “wrote a song about it with a jokey tone that felt off” (100). In this description, the public is unaware of the real risks caused by radiation, only “disappointment” at the idea that they will not be able to see weird radioactive frogs is mentioned. The conspicuousness of risk is not directly achieved as Freeman ironically comments on Small who only years later “became a Unitarian Universalist minister and wrote a very sincere song about Hiroshima” (100). By means of this conclusive remark, Freeman suggests again that the nuclear sublime and its mythos delay or impede environmental awareness and action.

More practically, the conflation between the imaginary of the weird and the atomic sublime shows an encounter between the imaginative and the material sublimes, between what is imagined—i.e., radioactive, and dangerous monsters—and what is seen—i.e., irradiated and toxic, but, in the end, regular-looking animals—, and the demystification of the former that eventually happen at some point in time and led Small to write his song about Hiroshima. Another compelling example of the contrast between imaginative and material aspects of the sublime is evoked in relation to another aesthetic category, the gothic, in both “The Ghost of the Homecoming” and “The Ghost of Wheat.” While, as previously discussed, Hales argues that “no gothic horror” could suffice to counter the nuclear sublime, Freeman suggests that the “phantoms” created by the “Wite-Out,” and the story of the “Ghost of the Wheat”—referring to “the spirit of a farmer whose land was forcibly taken by the government” to make space for the Manhattan Project—function as forms of resistance to the nuclear sublime. As representatives of the past, these ghosts transform the nuclear sublime into a form of “storied matter,” “a material ‘mesh’ of meanings, properties, and processes, in which human and nonhuman players are interlocked in networks that produce undeniable signifying forces” (Iovino and Oppermann 2014, 1–2). In other words, Freeman includes “The Ghost of Wheat” as “part of [her] nervous system, as well as the nervous system of Oak Ridge, unruly, a bit paranoid, sometimes matter, sometimes spirit” (48), which also becomes an emblem of the “pre-atomic past” (47). The gothic ghost, despite its white spirit-like look, epitomizes this web of “signifying forces,” as well as of the pre-atomic past, and the consequences of the post-atomic era, in a way that parallels Vizenor’s hibakusha’s ethical power. Ghost stories in Freeman’s memoir also complicate the visible/invisible binary, as does her approach to silence when she “realize[s] that silence is a kind of ticking too” (69). This quote also contrasts with Vizenor’s phrase “death by silence,” itself related to the politico-ethical power of the dead children, which highlights that radiation does not need to be seen or heard to affect non/human bodies. In that sense, Freeman ties in with Vizenor’s approach to the dichotomy absence/presence insofar as both of their imaginative representations of ghosts and silence emphasize the agential, animistic, and ethical power of ghosts.12 While the US government and the nuclear sublime, as both authors suggest, contribute to establishing secrets and lies which hide and confuse the risks of radiation, the tropes of absence and silence emerge in these works of non/fiction as effective critical tools that are complementary to the rhetoric of the sublime and serve to foster ecological awareness. Freeman’s innovation, however, lies in her attempt to combine such tropes with different aesthetic categories such as the sublime, the weird, and the gothic.

Still, one way of deconstructing or resolving the visibility/invisibility dichotomy while overcoming the limits of Western ocularcentric culture that stands out in Freeman’s memoir is her specific attention to the “lower” sense of touch and, to a lesser extent, the sense of smell. In “Hypercolor,” for example, she argues that “colors are not only known visually but are also felt” (98). “The absence of evidence of preteen mitts upon us or the nonexistence of our own handprints touching others,” she writes, “made us a kind of invisible, a failure, unable to make our mark” (98). In this extract, Freeman introduces a haptic dimension since the absence of our “handprints touching others” is responsible for what she refers to as “invisibility” or as a “failure” to achieve a complex understanding of the multiple “colors” defining our bodies and environments.

The potential of touch is also mentioned in “Atomic Mary and the Atomic Uncanny,” which brings together the nuclear sublime and the uncanny insofar as “the Atomic Mary statue on the grounds of St. Mary’s Catholic Church” that she depicts becomes “the oracle of the unthinkable”: in a state of admiration, Freeman imagines that by “trac[ing] the atomic by her feet with [her] index finger,” the statue would come to life, touch her and make her radiant (or radioactive) too (76–77). Touch serves the purpose of making the nuclear sublime—emblematized by the atom symbol on the statue—visible, of confronting the unthinkable.

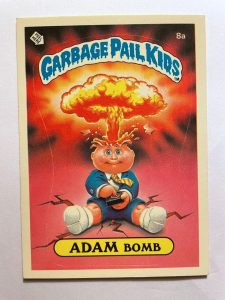

In a more tragi-comic tone, Freeman comments on the “Garbage Pail Kids” stickers trading cards and, more specifically, on the example of the “pressing” of the launch button in “Adam Bomb” (image 4): “The Garbage Pail Kids illustrated all kinds of terrible things that could happen to a person, hundreds of our unconscious fears laid out in bright colors” (104). Colors are mentioned as contributing to the unveiling of the “unconscious fears” that the nuclear sublime obscures. What is more, the sense of touch is involved because the cards are collectables, “malleable macabre objects” that “could be kept as a card or peeled off as a sticker and stuck almost anywhere” (104). The sense of smell is also evoked as “they smelled sweetly stale because of the brittle piece of pink bubble gum that came, like a stowaway, in their packaging” (104). These collectables were revelatory, especially “Adam Bomb,” which Freeman describes as “creat[ing] an explosion but also a pause” since “it exploded the continuum of history” (106). “The pressing” of the red button, she writes, “was a reminder of what could happen and a reminder of what already had” (106). Despite the grotesque and sublime aspects of the card, namely the explosion of Adam’s head (grotesque) resulting in a mushroom cloud (nuclear sublime), the act of pressing the button still feeds on the state of fear installed by the nuclear sublime but in a way that leads the author to question the historical and material consequences of atomic power: “Riding in the back seat of the twentieth century, I was acutely aware of the destructive power of nuclear technologies” (106). What is more, the Garbage Pail Kids contrast with the “all’s-right-with-the-natural-world” logic of the Cabbage Patch Kids that it spoofs, and the “pressing” of the button in “Adam Bomb” contributes to raising awareness of the possible (and imminent) dangers associated with nuclear weapons. With the risk of granting too much figurative meaning to the cards, one could also associate the name “Adam” with the original sin, which would imply that the creation of atomic weapons can put an end to humanity and, as the apocalyptical creaking ground on the image suggests, to the world as we know it. As a result, Freeman’s vignettes actively involve the senses of sight, touch, and smell to overcome the possible limits correlated with the absence/presence dichotomy, thus proposing effective resistance to the beguiling but dangerous nuclear sublime.

Conclusion: Mapping Common Ground Between Experimental Narration and Memoiristic Explorations

Various narrative and rhetorical approaches allow to represent and critique the atomic sublime and, more largely, nuclear culture. Vizenor’s complex metaphors, deployed in Ronin’s sections and then further explained by Manidoo Envoy, support the main goal Vizenor associates with survivance: creating a collective memory of a terrible nuclear history and culture that would not be stained by dominance or control over the human or nonhuman, imperialism, or hypocrisy. If kabuki theater is described as direct and engaging, as opposed to the rhetoric of the natural or nuclear sublime, Vizenor’s style remains highly metaphorical, abstract, and difficult to interpret. One may wonder if such complexity may not run the risk of over-aestheticizing the nuclear crisis and of confusing instead of informing readers, which would ultimately contribute to further embedding the mythos of the atomic sublime in our imaginaries and mindsets. Vizenor’s intricate approach to the narrative of nuclear culture, however, combines Anishinaabe and Japanese genres and traditions in a way that provides absence, mostly represented by the children’s ghosts, with agency and ethical power to counter dominant cultures. If the answers to the question as to how the nuclear sublime can be defeated may not have been found, Vizenor stresses that any attempt to find these answers will not be an easy task for both writers and literary scholars in that it will require a substantial conceptual apparatus that would best account for the environmental and (post)colonial dimensions of nuclear history.

.13 Even though they are scattered throughout the narrative arc, these metaphors presented in the format of vignettes are connected, which strengthens Freeman’s general argument that the atomic permeates “nervous systems,” bodies, and culture. Through her imaginative discussion of the pervasiveness of radiation, Freeman does not (merely) fall for the distant observation and (over-)aestheticization of nuclear phenomena in an approach that would have been comparable to the classical sublime. On the contrary, she demystifies the mythos of the nuclear sublime while shedding light on the devastating effects of inhabiting toxic places, which erases any hope for Kantian “aesthetic well-being” and represents the “atomic world” as a world in ontological crisis that is still far from achieving ecological stability.

Both works highlight a necessity for the “spirit of experimentation” that Bergthaller and others have identified as characteristic of the environmental humanities. While Vizenor draws on non-white worldviews to display the agential potential of the unseen nonhuman, Freeman explores new materialist thinking and various affects to achieve the conspicuousness of risks that are associated with the nuclear sublime. The metaphorical language, tropes of ethical absence and silence, non-linear structures, and references to non-dominant cultures, new materialism, and “lower” senses of touch and smell deployed in these literary works are examples of the many ways both experimental fiction and (eco-)memoir can contribute to critiquing or possibly debunking problematic aesthetics such as the nuclear sublime, no matter how firmly they have been established.

Works Cited

Alaimo, Stacy. 2010. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Amundsen, Fiona, and Sylvia C. Frain. 2020. “The Politics of Invisibility: Visualizing Legacies of Nuclear Imperialisms.” Journal of Transnational American Studies 11 (2), pp. 125–51.

Bartram, William. 2003. Travels of William Bartram. New York: Dover.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bergthaller, Hannes, Rob Emmett, Adeline Johns-Putra, Agnes Kneitz, Susanna Lidström, Shane McCorristine, Isabel Pérez Ramos, Dana Phillips, Kate Rigby, and Libby Robin. 2014. “Mapping Common Ground: Ecocriticism, Environmental History, and the Environmental Humanities.” Environmental Humanities 5 (1), pp. 261–76. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615505.

Burke, Edmund. 1998. A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Sublime and Beautiful. Edited by Adam Phillips. The Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Couser, G. Thomas. 2011. Memoir: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2009. “Radiation Ecologies and the Wars of Light.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 55 (3), pp. 468–98.

Derrida, Jacques. 1993. Spectres de Marx. Paris: Galilée.

Durkheim, Émile (1858-1917). 1990. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse : le système totémique en Australie. Paris: PUF.

Ferguson, Frances. 1984. “The Nuclear Sublime.” Diacritics 14 (2), pp. 4–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/464754.

Fisher, Mark. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater Books.

Freeman, Lindsey A. 2019. This Atom Bomb in Me. Stanford, California: Redwood Press.

Fressoz, Jean-Baptiste. 2021. “The Anthropocenic Sublime: A Critique.” In Climate and American Literature, edited by Michael Boyden, pp. 288–99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, Avery F. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Hales, Peter B. 1991. “The Atomic Sublime.” American Studies 32 (1), pp. 5–31.

Hecht, Gabrielle. 2010. “The Power of Nuclear Things.” Technology and Culture 51 (1), pp. 1–30.

Helstern, Linda Lizut. “Shifting the Ground: Theories of Survivance in From Sand Creek and Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57.” In Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, edited by Gerald Robert Vizenor, pp. 163–90. Lincoln and London: The University of Nebraska Press.

Howes, David, and Constance Classen. 2014. Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society. New York: Routledge.

Huang, Hsinya. 2017. “Radiation Ecologies in Gerald Vizenor’s Hiroshima Bugi.” Neohelicon 44 (2), pp. 417–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11059-017-0403-z.

Hurley, Jessica. 2020. Infrastructures of Apocalypse: American Literature and the Nuclear Complex. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Iovino, Serenella, and Serpil Oppermann. 2014. “Introduction: Stories Come to Matter.” In Material Ecocriticism, edited by Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann, pp. 1–17. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Jimenez, Chris. 2018. “Nuclear Disaster and Global Aesthetics in Gerald Vizenor’s Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57 and Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being.” Comparative Literature Studies 55 (2), p. 262. https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.55.2.0262.

Klein, Richard. 2013. “Climate Change through the Lens of Nuclear Criticism.” Diacritics 41 (3), pp. 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/dia.2013.0015.

Lippit, Akira Mizuta. 2005. Atomic Light: Shadow Optics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lombard, David. 2019. Techno-Thoreau: Aesthetics, Ecology and the Capitalocene. Macerata: Quodlibet.

Lynch, Tom. 2020. “Eco-Memoir, Belonging, and the Ecopoetics of Settler Colonial Enchantment.” In Dwellings of Enchantment: Writing and Reenchanting the Earth, edited by Bénédicte Meillon, pp. 119–29. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Masco, Joseph. 2006. The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Morton, Timothy. 2010. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

———. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Posthumanities 27. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Peeples, Jennifer. 2011. “Toxic Sublime: Imaging Contaminated Landscapes.” Environmental Communication 5 (4), pp. 373–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2011.616516.

Purdy, Jedediah. 2015. After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rash, Ron. 2004. Saints at the River. New York: Picador.

“Rozelle, Lee. 2006. Ecosublime: Environmental Awe and Terror from New World to Oddworld. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Saul, Hayley, and Emma Waterton. 2019. “Anthropocene Landscapes.” In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, edited by Peter Howard, Ian H. Thompson, Emma Waterton, and Mick Atha, 2nd edition, pp. 139–51. London and New York: Routledge.

Shaw, Philip. 2017. The Sublime. 1st paperback edition in 2006. London: Routledge.

Shukin, Nicole. 2020. “The Biocapital of Living—and the Art of Dying—After Fukushima.” Postmodern Culture: Journal of Interdisciplinary Thought on Contemporary Cultures 26 (2). http://www.pomoculture.org/2020/07/09/the-biocapital-of-living-and-the-art-of-dying-after-fukushima/.

Sokolowski, Jeanne. 2010. “Between Dangerous Extremes: Victimization, Ultranationalism, and Identity Performance in Gerald Vizenor’s” 62 (3), pp. 717–38.

Velie, Alan. 2008. “The War Cry of the Trickster: The Concept of Survivance in Gerald Vizenor’s Bear Island: The War at Sugar Point.” In Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, edited by Gerald Robert Vizenor, pp. 147–62. Lincoln and London: The University of Nebraska Press.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. 2003. Hiroshima Bugi: Atomu 57. Native Storiers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

———. 2008. “Aesthetics of Survivance: Literary Theory and Practice.” In Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, edited by Gerald Robert Vizenor, pp. 1–24. Lincoln and London: The University of Nebraska Press.

Wallace, Molly. 2016. Risk Criticism: Precautionary Reading in an Age of Environmental Uncertainty. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Wilson, Rob. 1989. “Towards the Nuclear Sublime: Representations of Technological Vastness in Postmodern Poetry.” Prospects 14 (October), pp. 407–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0361233300005809.

Yoneyama, Lisa. 1999. Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

1 Mobilizations of the natural sublime in arts are numerous, including in literature. My book Techno-Thoreau, for instance, offers a series of both secular (e.g., an analysis of a passage from Ron Rash’s Saints at the River) and religious (e.g., William Bartram’s description of wilderness as “untrammeled,” “divine,” and “infinite” in his Travels) examples of how it can be deployed (Lombard 2019, 20–32).

2 When it does not refer to the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty or of the sublime (i.e., “aesthetics”), the term “aesthetic” in Hales’s article and throughout this essay is related to issues of representation. Hales’s comment, for example, suggests that the atomic sublime offers pleasing or attractive representations of nuclear phenomena that are devoid of any critical outlook. As this essay will try to show, an embodied or multisensorial approach to landscapes can provide an experience that is no longer solely aesthetic but also affective because of the more diverse and complex affects and emotions it can produce.

3 By “Anthropocene Landscapes,” Saul and Waterton refers to “those that display the ravages of modernity’s violence” (2019, 143). This violence can take various shapes, ranging from unfettered deforestation to human waste, and pollution or to the destruction of biodiversity. I would argue, however, that the adjective “Anthropocene” does not inevitably entail that humans are destructive actors in any environment but that their participative and possibly transformative forces in the landscape they occupy or inhabit can no longer be disputed.

4 Bergthaller et al. argue that the representational and ontological challenges raised by the Anthropocene call for experimentations in the field of the environmental humanities, that is for theoretical and methodological approaches which explore a wider spectrum of, for example, cultures, traditions, disciplines, and narrative/rhetorical techniques (Bergthaller et al. 2014).

5 As historians David Howes and Constance Classen argue, the “lower” senses of taste, touch, and smell have “attract[ed] little attention in Western society” compared to the higher senses of sight and hearing, whereas all of their sensations participate in the same “interactive web of experience” that complicates and enriches “sensory practices” (2014, 5). Analyzing descriptions of feelings, emotions, and affects produced by multisensorial experiences in literary works such as Freeman’s memoir opens the way for innovative, more nuanced, and critical interpretations of the sublime and of nuclear culture.

6 The White Earth Indian Reservation is located in northwestern Minnesota and was created in 1867. It is still inhabited by the White Earth Band, one of the six bands that constitute the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (Ojibwe or Anishinaabe are other words for “Chippewa”).

7 Although the Anishinaabe borrowed elements from Christianity, among other religions, Alan Velie highlights that Vizenor understands American Christianity’s storytelling as “humorless” and “tragic,” which contrasts with “trickster stories” and their “communal” and “comic” components (2008, 157). Linda Lizut Helstern also argues that references to Christianity in Hiroshima Bugi contribute to Vizenor’s project of “deconstruct[ing] ideologies” of “peace and victimry” as well as “the true believers who perpetrate them” (2008, 183).

8 The ghosts’ ethical presence echoes Jacques Derrida’s formulation of “hantologie” (“Hanter ne veut pas dire être présent”), which also explains how past theories and cultures can still influence and/or transform the present (Derrida 1993, 255).

9 In Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuses, Durkheim questions the idea of “survivance” in animistic worldviews, calling it “hardly intelligible” insofar as it suggests that the physical body can continue to live as a spirit that would be its “double.” Vizenor, however, seems to suggest in Hiroshima Bugi that a form of materialized absence such as a ghost could exist and shed light on important political and ethical issues (Durkheim 1990, 86–87).

10 In her memoir, Freeman explicitly refers to Jane Bennett’s theory of “vibrant matter,” which “articulate[s] a vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans to see how analyses of political events might change if we gave the force of things more due” (2010, viii).

11 This quote alludes again to Derrida’s take on hauntology, to which I refer in the first section of this essay.

12 This approach echoes sociologist Avery F. Gordon’s book Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, in which she also challenges the understanding of ghosts as silent absences. Absences can be “seething,” she writes, presences can be “muted,” and ghosts, through what she terms “haunting,” can act as active and visible reminders of forms of “social violence” that occurred in the past (2008, xvi–21).

13 The effect of such “hyperobjects” are even less possibly perceived in time, being often outcomes of “slow violence,” that is a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, […] of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, [and] that is not viewed as violence at all” (Nixon 2011, 2). It is also worth noting that these two concepts, which are frequently quoted in ecocritical scholarship, echo the incommensurability and ineffability of the sublime.